Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

Welcome to the Saas Museum. I’m Evelyne…

… and I’m Beat.

Together, we’ll guide you through the exhibition rooms in the Saas Museum.

You will learn how the Saas people lived in olden times, what famous writer Carl Zuckmayer’s study in Saas-Fee looked like and how tourism came to the Saas Valley.

Before we turn to the exhibition rooms, let’s leave the Saas Museum building to take a look at this typical Valais house from the outside.

We hope you learn lots about the history of the Saas Valley.

Outdoor space

Outdoor space

Outdoor space

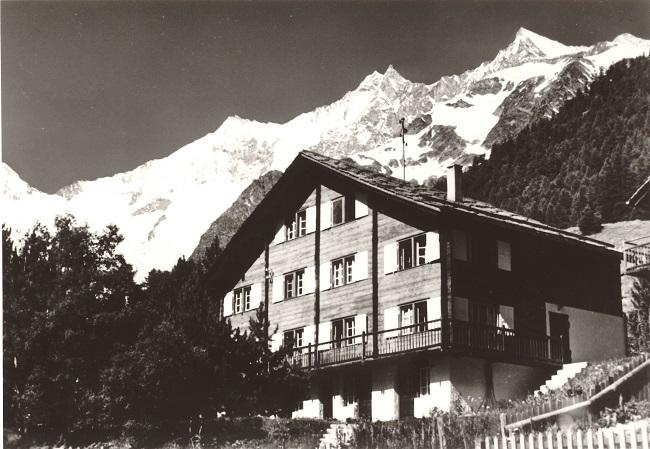

We are standing in front of one of the best-preserved traditional Valais houses in the Saas Valley. An initiative by Werner Imseng, the village chronicler at the time, saw the building converted into the Saas Museum in 1983 and also moved a few metres back from the main road. The building had previously been a vicarage. In the past, floors were also used for a schoolhouse and as an exhibition room for a local history museum.

The building was constructed in 1732. A further floor was added in 1855. Alois Burgener, the former parish priest, lived here until 1980. Alongside his pastoral duties, he was also a farmer.

Typical of the Valais building style are the brick substructure and the wooden building built on top. The stone substructure once housed the cellar, while the heated parlour was located in the wooden building. To prevent fire, the kitchen on the first floor was also walled in with stone against the slope. The roof gable is decorated with the initials of Mary and Jesus to place the house under divine protection.

There is a more recent fountain to the right of the entrance to the Saas Museum. As is often the case with Valais fountains, it is divided into two pools. The first pool was used by the locals for water, the second basin was used as a drinking trough for animals.

Walking a few metres to the left of the road, we come to a road cross typical of the Saas Valley.

This cross was originally located on the other side of the Saas Museum, where two roads meet. These crosses were erected at important road junctions in the 18th century.

The roadside crosses in the Saas Valley symbolise the suffering that Jesus endured during his crucifixion. In German, these are known as Freitagschristus (Friday Christ). They remind Christians to keep Sunday and church holidays holy, as otherwise Jesus would suffer pain as he did at the crucifixion.

Saas road crosses are full of symbols. If we look at the crossbeam of the cross, we see dice. These represent the drawing of lots for Jesus‘ clothes. The ladder is a symbol for the taking down of the body from the cross, while the wooden hand symbolises the slaps Jesus endured during his interrogation. The rooster at the top of the cross is a reminder of Peter’s denial of Jesus.

On the right of the road cross we see a bronze bust of the Hindu teacher and social reformer, Swami Vivekananda. This was unveiled in 2013 to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth. In 1896, Swami Vivekananda spent two weeks in Saas-Fee and was deeply moved by the beauty and grandeur of the glacier village. Saas-Fee reminded the 33-year-old of his north-east Indian homeland. In a letter, he described Saas-Fee as a „miniature Himalaya“. Vivekananda rose to fame as a mediator of Hindu religious practices in the West. Three years before his visit to Saas-Fee, he gave a highly acclaimed speech to the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago.

If you would like to find out more about Swami Vivekananda and his time in Saas-Fee, go to the story number 3. Otherwise let’s go to the first floor of the Saas Museum.

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda

At the end of the 19th century, the tourist industry was in its infancy in Saas-Fee when the Indian monk Swami Vivekananda stayed at the Grand Hotel for a fortnight in August 1896. During his stay, he tried to use meditation to forget the world around him. At least that’s how he described his plans in a letter he sent in Saas-Grund before arriving in the glacier village.

In the years before he came to Saas-Fee, the disciple of the famous Hindu mystic Ramakrishna had more or less single-handedly introduced Indian religious beliefs to the West. Including yoga.

„If you want to understand India, you have to study Vivekananda,“ said the Indian Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore. Even today, Vivekananda is recognised as a national hero in India and is enshrined in the collective memory.

Swami Vivekananda did not come to Saas-Fee alone. Two schoolgirls came with him to the glacier village. In the solitude of the mountains, the three of them developed the idea of a spiritual centre in the Himalayas, which still exists today under the name „Advaita Ashrama“.

Vivekananda was struck by the calming influence of the mountains in the Saas Valley and in a letter enthused about delightful walks in the forest and the beautiful scenery, nestled in the middle of three glaciers. It was in this landscape that he seemed to be able to detach himself from earthly feelings and attachments, as he wrote in another letter.

Saas cultural history

Saas cultural history

Saas cultural history

Before tourism came to the Saas Valley, the inhabitants of the valley led a frugal life centred around agriculture. Sheep, goats, pigs and cows provided the inhabitants with meat, and potatoes and grain, especially barley, were grown in the fields. In this room we can see the tools that were used in everyday life.

The ash sieve, a replica of which hangs on the wall near the door, is worth a special mention. In spring, the ash sieve was used to accelerate the melting of the snow. On the wall to the left of the door is a photo of a Saas-Fee man using the ash sieve.

The Saas people were very resourceful. But why does the snow melt faster when ash is poured on top?

It’s to do with the physical properties of ash. Ash has a high heat capacity, so it absorbs heat from the environment. This warms the snow. At the same time, the ash reduces the humidity around the snow, which also speeds up the melting process.

While the Saas men climbed four-thousand-metre peaks as mountain guides or worked as skilled bricklayers on building sites, farming was probably left in the hands of women, as you can see from the photos on the walls.

That’s how it was. Women played an important role in Saas agriculture. In summer, the men worked as mountain guides, bricklayers, labourers or pack mule handlers, often outside the Saas Valley. During this time, the women took care of the farming. Until the second half of the 20th century, it was common for women to carry heavy loads of hay from the field to the barn in summer. Even the children were involved in everyday farming life. They looked after the animals. Let’s go into the next room now.

On the left-hand side we see a water channel, or Suone, as it is called in the Upper Valais. In other German-speaking regions it is also known as a Wuhr or Fluder.

The Saas Valley is one of the driest regions in Switzerland, enjoying 300 days of sunshine. However, there was still plenty of water thanks to the glaciers. Water channels were created to use this to water the fields. Water was channelled onto the fields using paddles. However, watering the fields was strictly forbidden on Sundays and public holidays.

How did people know when they were allowed to use the water for watering?

This was recorded in books, called „water books“. In the Saas Valley, there was also a tradition, which has been documented across the whole of the Upper Valais, of recording important completed tasks or accounts on „tessel“. Tessels are small pieces of wood with notched marks recording legal facts – for example, whether the water bailiff’s order to repair a water channel had been followed. We can see these tessels on display here.

It was vital to water the meadows so that anything could grow at all at this dry altitude. What did the Saas people eat in the old days?

The people of the Saas Valley were largely self-sufficient for centuries. With a few exceptions, people lived on what nature gave them. One exception was rice. Local men who helped make hay in neighbouring Macugnaga in Italy over the summer were paid around 20 kilograms of rice, which they brought back to the Saas Valley.

But 20 kilograms of rice didn’t satisfy their hunger for long.

Meat was therefore one of the staple foods. They slaughtered the animals themselves. The butchery began on 16 October, Saint Gallus day. After this, relatives would be invited to a barbecue. The traditional Saas dish Greibe, also known as Grieben in standard German, is made by putting offal, minced meat and bacon in a pan and seasoning it with sugar. The whole family ate from the same pan – each with their own spoon.

People still talk about Greiwe in Saas Valley, even if they are rarely cooked. The Saas sausages are quite different. They are still on everyone’s lips.

They are also very tasty. Sausages have a long-standing tradition in the Saas Valley. Saas sausages are famous far beyond the borders of the valley. As the people in the Saas Valley were poor, sausages here were made with more vegetables than in other places. Some people claim that it is therefore safe to eat Saas sausages even on a Friday, the Catholic fasting day. It is, after all, a low-meat vegetable sausage. Each family has its own recipe for tasty Saas sausages. Beef, pork, bacon, potatoes, onions, various spices and beetroot are used to give the air-dried sausages their characteristic purple colour. Let’s leave this room and visit an old Saas parlour.

How the Saas people of old lived

How the Saas people of old lived

How the Saas people of old lived

We are now in an authentic Saas parlour. The main material used for the interior was local larch. Living conditions were cramped. Several children often slept in the same bed to save space, perhaps in a pull-out trundle bed, as we can see in the room. The Saas people used a soapstone stove to heat their home, which could store heat well. They were made from local soapstone by local stove makers. It was lit in the kitchen. Soapstone stoves were decorated, perhaps with family coats of arms, the initials of the owners, religious symbols or the year they were built. On the bench by the stove, you could warm up in the cold or sit and smoke your pipe in a cosy atmosphere.

Winters in the Saas Valley can seem endless. How did the locals spend the long, cold evenings?

On evenings in the old days, people prayed the rosary, enjoyed a cosy chat, known as a Hengert, or played card games. In the winter months, they would also do this outside their own home, in an evening get-together known as an Abundsitz. In every hamlet in the Saas Valley there was an Abundsitz, parlour where locals would meet after the day’s work, tell each other stories and tales, drink, smoke and play games together.

There is a pack of cards on the dining table. Are these Troggen cards?

Yes. Troggen was the traditional card game of the Saas Valley. We can see the playing cards from this baroque tarot game on the dining table. The tarot game was invented in northern Italy in the 15th century. In the early 16th century, soldiers from Valais discovered the game in Italy and brought it back to their homeland. Including to the Saas Valley. At the beginning of the 20th century, Troggen was still played in the parlours of Saas until it was finally replaced by Dutch game, Jass.

I spotted a clock with an engraved name by the front door. Can you tell us something about it?

Sure. The clock dating from 1842 belonged to parish priest Johann Josef Imseng. Imseng made a name for himself in several fields. He welcomed guests to his vicarage in Saas-Grund and then lobbied for the construction of the first hotels. He is therefore regarded as the founder of tourism in the Saas Valley. He also worked as a mountain guide and botanist. Imseng, the tourism priest, also earned a place in the history books as Switzerland’s first skier. One winter’s day in 1849, he tied wooden planks under his feet and used them to descend from Saas-Fee into the valley so that he could provide religious assistance to a dying man in Saas-Grund before it was too late.

Johann Josef Imseng was a real jack-of-all-trades. Are there places in the Saas Valley where this tourism pioneer is commemorated?

If you look through one of the windows in this room towards Allalin and Alphubel, you can see the house where Johann Josef Imseng was born. There is a plaque on the front of the house commemorating the tourism priest. The memorial plaque can only just be seen from here. There are also other places where this tourism pioneer is remembered. He has been honoured with a monument on the village square in Saas-Fee. This statue near the church depicts Imseng in his cassock holding the ice axe he first used to guide tourists up the four-thousand-metre peaks in the Saas Valley. In Saas-Grund, there is a memorial exhibition on Johann Josef Imseng in the old vicarage. Let’s move to the next room now.

Spinning, knitting and weaving were part of everyday life for Saas women. A lively hengert, a friendly chat, was always part of these activities.

What clothes did women make themselves in those days?

All everyday clothes, aprons, scarves, carpets and bedspreads were woven by hand even around 1900, and the clothes were made from „drill“ fabric. This material was supplied by the local sheep, although the wool quality of the Saaser Mutten, a distinct breed typical of the Saas Valley, is frankly quite poor.

The loom is a powerful tool. It’s hard to imagine that all the families in the Saas Valley had the space and money for such a thing.

You’re right. Only a few households had a loom as large as the one we see in this room. The women in the village would share a few looms among their larger family.

Isn’t it amazing how many Christian symbols there are in this room?

Today, these symbols do indeed seem excessive. It’s clear that the Christian faith was a constant source of guidance for the Saas people for a long time. It gave structure to everyday life and answers to the big questions of life. On the wall, for example, you can see a picture of a clock from the middle of the 19th century. The story of the Son of God, from his birth to his death, is illustrated in 24 stations. Next to it, we see in another picture how the forces of good and evil wrestle for the soul of a dying man at his bedside. The devil is the one who ultimately wins the soul. In earlier centuries, the people of the Saas Valley were in constant fear of an unexpected and unplanned death where the Last Sacrament could not be administered. Now let’s go to the kitchen.

In old Valais houses, the kitchen was walled in to give protection from fire. Traditionally there was an open fireplace, the Trächu.

Compared to a modern domestic kitchen, the Trächu could not really be used for many different types of food preparation. So what did the Saas people eat over 100 years ago?

For breakfast there was meat soup. Sometimes for a change, there would be cheese, bacon, butter and rye bread. Up until the end of the 19th century, there were one or two bakehouses per village in the Saas Valley. They contained bread ovens that were available to the community. Before 1897, there was only one bakehouse in Saas-Fee, where the families of the village baked rye bread twice a year. The rye bread was stored up in the attic.

And what was served for lunch and dinner?

They ate potatoes, cabbage and carrots for lunch. It was usually served with boiled mutton or pork. In other words, they ate the food that was available in the Saas Valley. Another popular lunch was polenta. The Saas Valley was not suitable for growing maize. The Saas people bought their maize at the market in Visp or imported it from Italy. In the evening people ate meat soup again, as well as barley and polenta soup. For a change, they might have potatoes and skimmed milk or cheese with rye bread in the evening. Lent was a special time: the Saas people abstained from eating meat for 40 days. Now let’s go upstairs. To the study of the writer Carl Zuckmayer.

Carl Zuckmayer's Study

Carl Zuckmayer's Study

Carl Zuckmayer's Study

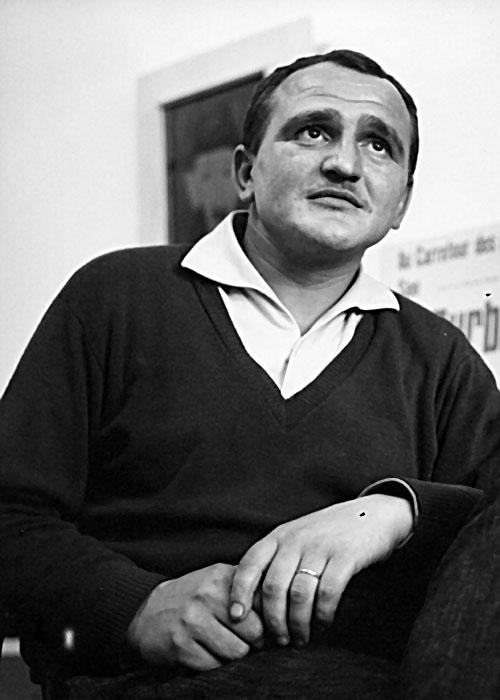

„When my wife and I walked up the chapel path from Saas-Grund to Saas-Fee with our rucksacks one evening in July 1938, we didn’t realise we were going home.“

The influential writer and playwright Carl Zuckmayer wrote these lines in his autobiography Als wär’s ein Stück von mir (A Part of Myself). In July 1938, Carl Zuckmayer and his wife, the Viennese Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer, spent a few days on holiday in the Upper Valais, escaping the summer heat on Lake Geneva – their temporary home after the National Socialist seizure of power in Austria. During this holiday, they found themselves in the Saas Valley one day. At that time, the road only went as far as Saas-Grund. They climbed the last section to the glacier village on foot. As soon as he laid eyes on them, the mountains of Saas-Fee had a powerful effect on Carl Zuckmayer. In his autobiography, he wrote,

„I am suddenly confronted with a sight that I have never seen before. You are standing at the end of the world and at the same time at its origin, at its beginning and in its centre. An enormous silver frame, closed in a semicircle, to the south by snowy peaks arranged in an inexplicable harmony, to the west by a chain of Gothic cathedral towers. At first, all you can do is look up, it takes your breath away. „‚Here,“ said one of us – „If only you could stay here!“

Another 20 years were to pass before this dream was realised. One year after their first visit to Saas-Fee, the Zuckmayer family were forced to flee into exile in the USA. They lived as farmers for a long time in the state of Vermont.

It was not until 1947, nine years after his first visit to Saas-Fee, that Carl Zuckmayer returned to the glacier village. He went on to travel to the Saas Valley 14 more times before Carl and Alice Zuckmayer finally moved their home to Saas-Fee in 1957, to the Vogelweid larch wood house in Wildi hamlet. It was to be their last home. Carl Zuckmayer died in 1977, his wife Alice in 1991.

At the end of the 1950s, when Carl Zuckmayer chose to make Saas-Fee his new home, he was the most successful German playwright in the West. His plays such as Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (The Captain of Köpenick) and Des Teufels General (The Devil’s General) were performed on the great German stages and were also successfully made into films. He also wrote stories and poems. Zuckmayer achieved his breakthrough in 1925 with his play Der fröhliche Weinberg (The Happy Vineyard). He was 28 years old at the time.

Why does he have a study in the Saas Museum?

After Carl Zuckmayer’s death, his estate donated his study to the community so that it could be displayed in the Saas Museum. His daughter Maria Winnetou Guttenbrunner-Zuckmayer arranged the room just as her father had once furnished it in the Vogelweid house.

Would you like to take a closer look together at some of the key items in the study?

Sure. Plays such as Katharina Knie and Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (The Captain of Köpenick) were written on the heavy oak desk at the centre of the room back in the 1920s and early 1930s in Henndorf, Austria. In Saas-Fee, Zuckmayer wrote Das Leben des Horace A.W. Tabor (The Life of Horace A.W. Tabor), Der Rattenfänger (The Pied Piper) and his autobiography „A Part of Myself“ on this desk.

There is a letter from Carl Zuckmayer to his daughter Winnetou on the desk. Next to it are what are known as consumption booklets. The locals would write their unpaid bills at the grocery shop in them. Zuckmayer, however, used the little consumption books as notebooks on his daily walks through the Saas-Fee larch forests.

On the right of the desk we can see Zuckmayer’s death mask, his guitar, which he loved to sing along to, a drawing of Mainz, where he grew up, and a photo of the writer Gerhart Hauptmann, the most famous proponent of naturalism, in whose footsteps Zuckmayer followed with his folk play, The Happy Vineyard.

On the right-hand wall is an old Salzburg farmer’s cupboard, and on the wall by the entrance is a display with pewter plates and a bundle of straw as a bouquet of flowers, which Zuckmayer was given by a clown from the Swiss National Circus Knie.

Carl Zuckmayer was a passionate collector of minerals and butterflies, as can be seen from other objects in his study. There are also some animal bones on the left of the table that he found in the American forests.

Carl Zuckmayer and Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer are buried in the cemetery in Saas-Fee.

If you would like to find out more about Carl Zuckmayer and Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer’s life in Saas-Fee, go to story number 7. Otherwise let’s move on to the Alpine relief.

Carl Zuckmayer and Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer's life in Saas-Fee

Carl Zuckmayer and Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer's life in Saas-Fee

Carl Zuckmayer and Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer's life in Saas-Fee

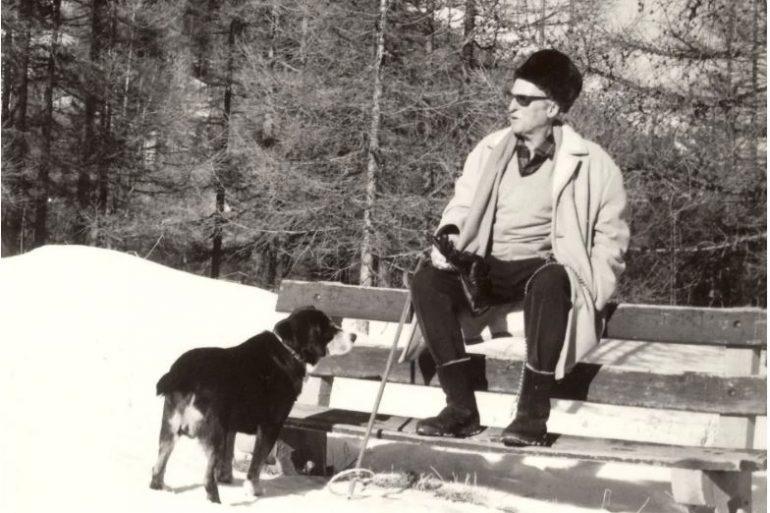

„Where is home? Where you were born or where you wish to die“, asks Carl Zuckmayer in his autobiography „A Part of Myself“. After years of exile, Alice and Carl Zuckmayer found a home again in Saas-Fee. They quickly integrated into village life. On his 65th birthday, the community presented Carl Zuckmayer with the „Ehrenburgerbrief“ (Honorary Citizen’s Letter), the greatest possible recognition that can be given to an immigrant in Saas-Fee.

Carl Zuckmayer had a regular daily routine in Saas-Fee. He worked in the mornings until 11.00 a.m. before going for his daily walk. One of his favourite routes was the Wildi-Bärenfalle-Melchboden-Café Alpenblick, a route that can now be followed as the Carl-Zuckmayer-Weg. There are quotes by Carl Zuckmayer engraved on serpentine stones along the way.

Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer was always in the shadow of her famous husband during her life. Her autobiographical memoir „Die Farm in den grünen Bergen“ (The Farm in the Green Mountains) enjoyed great success at the end of the 1940s. She wrote more books in Saas-Fee, including „Das Scheusal“ (The Monster), another autobiographical story about a dog that she inherited from a quirky aunt. This book also found a large number of readers.

Both Mr and Mrs Zuckmayer loved life in the seclusion of the Saas Valley. „Every day that I don’t spend here in Saas-Fee is only half a day for me. Only here do I live fully,“ said Carl Zuckmayer in January 1973. He made the world travel to the glacier village so that he wouldn’t have to leave the Saas Valley. Among the guests Carl Zuckmayer welcomed to Vogelweid were renowned figures such as the composer Paul Hindemith, the mountaineer and film-maker Luis Trenker and the German Federal President Theodor Heuss, a drawing of whom hangs on the left-hand wall of Zuckmayer’s study – from Chillon Castle on Lake Geneva.

Alpine relief

Alpine relief

Alpine relief

We are standing in front of an impressive mountain relief. Saas-Fee and the Saas Valley are a bit hidden at the very edge of the glacier exhibit.

Have you found them?

What about now?

Saas-Fee really is a bit on the edge.

The centre of the relief is not the Saas Valley, but Monte Rosa, the Queen of the Alps. This mountain massif has nine peaks over 4,000 metres high. The highest is Dufourspitze at 4,634 metres – the second highest mountain in the Alps after Mont Blanc and therefore in Western Europe.

This relief shows the mountains and villages around the Monte Rosa massif. You can hike around the mountains over nine days on the „Tour Monte Rosa“. Saas-Fee is one of the stage towns.

If you start the „Tour Monte Rosa“ from Saas-Fee in an anti-clockwise direction, you will reach Zermatt after three stages. The first stage to Grächen cannot be followed on the relief. This section leading north is missing. From Grächen, you hike south again, so the relief partly shows the two-day route towards Zermatt with an overnight stay in the Europa Hut. On the first day you walk with a view of the majestic Weisshorn, on the second day the Matterhorn gets ever closer. In Zermatt, you can choose to head towards the Theodulspass, a glaciated border pass between Switzerland and Italy, which is over 3000 metres high and was used as far back as the ancient Romans.

The next stage stop is St. Jacques in the Aosta Valley. The impressive glaciated southern side of the Monte Rosa massif has a prominent place at the end of the valley. The four Italian villages that you pass through on the „Tour Monte Rosa“ are picturesque Walser villages. The people of Walser were originally from the Upper Valais. They emigrated from their mountain villages to other Alpine regions in the 13th and 14th centuries, including the nearby Aosta Valley and Piedmont. They kept the typical Valais log construction style and the typical Alemannic dialect.

Walser German has been passed down from generation to generation in the Walser villages in the Aosta Valley and Piedmont over the last 800 years. Now it is dying out. There are only a few older people who still speak Walser German and so speak almost the same dialect as the people in the Saas Valley.

Gressonay is the next stage town on the „Tour Monte Rosa“. As is typical of Walser villages, the village is divided into several hamlets spread throughout the valley. Gressonay and neighbouring Alagna are known as a hiking and skiing area. This next stage town is not part of the Aosta Valley any more, but of Piedmont. Located in Valsesia, this Walser village was home to famous master builders, such as Ulrich Ruffiner, who was born around 1480 and built several important churches and bridges in Upper Valais.

From Alagna you cross the Turlo Pass to reach the Walser village of Macugnaga. This village, situated on the east face of Monte Rosa, the longest ice wall in the Alps, has always been of great significance for the Saas Valley. There have been many exchanges between the Saas Valley and Macugnanga over the centuries. Until well into the 20th century, goods such as tobacco, coffee and the sweetener saccharin were smuggled over the Monte Moro Pass, which connects the Mattmark area in the Saas Valley with Macugnaga.

The gold mine in Macugnaga, which was operational until 1961, was a source of income for many Saas people in the 19th century. The family of mountain guide Matthias Zurbriggen, born in Saas-Fee in 1856, was no exception and emigrated to Macungnaga. Matthias Zurbriggen is regarded as one of the most prominent mountain guides at the turn of the 19th century. He will be shown in more detail in the next exhibition room.

The „Tour Monte Rosa“ then heads back to the Saas Valley over the Monte Moro smugglers‘ pass. You first reach the Mattmark area, once an important alpine pasture area for Saas cattle farming, today a local recreation area with an artificial reservoir built in the 1960s for electricity generation. From there, the route leads via Saas-Almagell back to Saas-Fee.

Monte Rosa is not as significant in the mountain landscape of the Saas Valley as it is in Zermatt or Macugnaga, where this mountain massif is very prominent. Monte Rosa is too hidden in the Saas Valley in the Mattmark region. However, you can still enjoy a beautiful view of part of the massif, from Hohsaas in Saas-Grund and Heidbodme in Saas-Almagell.

The idea of opening up the entire „Tour Monte Rosa“ as a ski area has been discussed many times. This would create the largest and one of the snowiest ski resorts in the world.

As you can see from the relief, the Saas Valley is surrounded by towering four-thousand-metre peaks. The Allalin and Weissmies mountains are among the easiest four-thousand-metre peaks to climb, while the imposing Mischabel chain above Saas-Fee includes the Dom, the highest mountain lying entirely on Swiss soil. It is 4,546 metres high. The Dom (meaning cathedral) was named in honour of a canon of Sitten, Josef Anton Berchtold. This priest from Upper Valais provided important support for the Valais land survey and Swiss cartography.

Other mountain names in the Saas Valley are more mysterious. Could the names for Allalin or Mischabel come from Saracens who were based in what is now St. Tropez in the 10th century and later occupied Alpine passes up the Rhone – including those in the Saas Valley? Mischabel sounds similar to the Arabic Ma‘ Djabal, which means water mountain or mountain of water, and Allalin is similar to the Arabic words for spring or heights. Modern linguists, however, are critical of Saracenic naming.

Close to the relief is an exhibition about glaciers. Glaciers have shaped the history of the Saas Valley for centuries. Until the end of the Little Ice Age in the middle of the 19th century, the tip of the Fee glacier reached right up to the edge of the village. In 1822, people from Saas-Fee erected a cross where the Felskinn valley station is located today to prevent the glacier from advancing any further.

At the beginning of the tourist boom at the turn of the 20th century, local children even fetched ice from the glacier in the summer months for the Saas-Fee hotel industry. In recent decades, the glacier has declined massively. The glaciers are still extremely important for the Saas Valley, both in terms of water supply and the stability of the mountains, but also from a tourism perspective.

History of Tourism in the Saas Valley

History of Tourism in the Saas Valley

History of Tourism in the Saas Valley

Beat, who do you think were the first tourists in the Saas Valley?

Was it the British alpinists who were the first to climb the Saas mountains in the middle of the 19th century?

Of course, they were very important for the development of tourism. But it was not the British who were the reason for building the first hotels.

Hm, to be honest, I’m in the dark. Tell me.

Before British alpinists, naturalists, botanists and painters came to explore the beautiful landscape of the Saas Valley. Even earlier, mule drivers came to the Saas Valley and pilgrims visited the nearby pilgrimage site of Varallo on Lake Orta. The local family name Bilgischer is a reference to pilgrims‘ parlours. They used to be called „Anderpilgerstuben“.

Is there any written evidence of the first tourists?

Very little. The Bernese naturalist Siegmund Gruner was not very fond of the natural beauty of the Saas. In 1778, he described the mountains of the Visp valleys as the „most horrible wilderness in Switzerland“ and like the „Swiss Greenland“. Painters and botanists then walked through the mountain landscape of the Saas Valley with fresh eyes. They recognised the beauty of the region. The Saas Chronicle records that Abraham Thomas from Bex in Vaud canton was the first botanist to come to the Saas Valley in 1795.

Where did these first guests stay?

Father Johann Josef Imseng, who we already encountered as the first skier in Switzerland, hosted tourists in his vicarage in Saas-Grund. In 1833, Moritz Zurbriggen from Saas-Grund rebuilt his house to accommodate visitors and hung a sign with the words „Gasthaus zur Sonne“ (Sun Inn) at the entrance. The Hotel Monte Rosa opened in Saas-Grund in 1850 at the request of Father Imseng and six years later, again following a suggestion by Father Imseng, the Hotel Monte Moro opened. As the Mattmark area was a particularly attractive landscape and transit area to Italy at this time, Imseng himself commissioned the construction of a hotel in the area in 1856.

This provided the infrastructure for the first alpinists in the Saas Valley.

Exactly. Amazingly, there were no hotels in Saas-Fee until the end of the century. The alpinists had to walk back to Saas-Grund after their tours in Saas-Fee. However, in 1881, the local community in Saas-Fee took matters into their own hands and ordered the construction of the first hotel, the Hotel Dom, near the church. In the years that followed, locals also built hotels in Saas-Fee, the Hotel Bellevue and the Grand Hotel. They were large white Belle Epoque boxes that dropped anchor in Saas-Fee like large steamships. Let me ask you, as a keen mountaineer, What do you know about the first ascents of the four thousand metre peaks in Saas and about the local mountain guides?

Oh. I could keep you entertained with mountain stories for an entire „Abundsitz“. One thing is for sure though, many a Saas man honed his mountain skills as a chamois hunter on the steep slopes of the Saas Valley. The British alpinists regarded these skills highly. Johann Josef Imseng, the Saas mountain-loving priest, climbed the mountains together with his porter and servant, Franz Andenmatten from Saas-Almagell. He succeeded in making the first ascent of the Allalin and Lagginhorn together with the English alpinist Edward Levi Ames. Imseng’s servant Franz Andenmatten proved to be a very talented mountaineer. He made further first ascents.

So, was it the British alpinists who introduced the Saas people to the idea of climbing the mountains?

That’s right. For a while, the crème de la crème of the British mountaineering scene frequented the few hotels in Saas. Edward Whymper, the first person to climb the Matterhorn, conquered the Weissmies, and Leslie Stephen, father of the famous writer Virginia Woolf, and whose book earned Switzerland the title „Playground of Europe“, was the first person to climb the Alphubel.

Besides Imseng and Andenmatten, were there any other local mountaineers who achieved fame in the annals of alpinism?

Two in particular are worth mentioning. One is Matthias Zurbriggen, who moved as a child from Saas-Fee over the Monte Moro Pass to neighbouring Macugnaga, where his father worked in the gold mine. Matthias Zurbriggen is considered one of the most impressive mountaineers at the turn of the 20th century. Zurbriggen mastered his skills on his native Monte Rosa east face in Macugnaga. Later, he travelled the world. He undertook expeditions in Karakoram, travelled alone in India and Australia and just missed the first ascent of Mount Cook in New Zealand by a few days in 1894. He achieved an impressive first ascent in Argentina in 1897. He was the first person to reach the highest mountain on the American continent, the 6958 metre-high Aconcagua in the Andes.

Why do we know so much about his life?

Matthias Zurbriggen wrote an autobiography of his experiences entitled „Von den Alpen zu den Anden“ (From the Alps to the Andes). The original Italian manuscript was lost for a long time. In 2015, one of Matthias Zurbriggen’s descendants found the original manuscript in his cellar in the USA and donated it to the Saas Museum.

Who was the second mountain guide who also deserves a place in the mountaineering pantheon?

Alexander Burgener. Born in 1845, he grew up in modest circumstances in the hamlet of Huteggen at the mouth of the Saas Valley. Like other mountain guides in Saas, he started his career as a goat herder and chamois hunter. He later became known as the „King of Mountain Guides“, a title he shares with the Bernese mountain guide Melchior Anderegg. Like Zurbriggen, Burgener also went on expeditions – both to the Andes and the Caucasus. In the local mountains, he achieved several difficult, spectacular first ascents, such as the Zmuttgrat on the Matterhorn and the Teufelsgrat on the Täschhorn.

I’m amazed at how well-travelled the mountain guides were back then. There’s also the interesting question of how the guests came to the Saas Valley in the first place.

Travelling to the Saas Valley was arduous. If you didn’t want to walk, you could use mules or strong men who carried guests into the Saas Valley on carrying chairs or, for the particularly well-off, in sedan chairs. The road from Stalden to Saas-Grund was only built in the 1920s. The road from Saas-Grund to Saas-Fee was opened in 1951. Until then, the mules did a good job. They peaked in number in the interwar years. In 1933, there were no fewer than 126 mules in the Saas Valley.

It’s hard to imagine that today. Post buses run every half hour from Visp to Saas-Fee.

The time taken to travel to Saas-Fee has been massively reduced over the last 100 years. If you wanted to travel from Bern to Saas-Fee in 1906, you had to take the train via Lausanne to Stalden and then, after a journey of over six hours, walk another five hours from Stalden to Saas-Fee. The journey from Bern to Saas-Fee now takes less than two hours since the opening of the NRLA base tunnel. Let’s go into the next room now. Evelyne, do you think you could win the Allalin Race with those old wooden skis hanging on the wall?

Since I probably wouldn’t manage a single turn, I would be certain of victory. But seriously, the first winter guests probably came to the Saas Valley on skis like these in 1898. It was another 50 years before the first ski lift was built.

Surely people didn’t wait for the first ski lift to go skiing?

Definitely not! The locals had been passionate skiers for decades. Some winters, the local authority lent skis to primary school pupils for free over the winter. The local authority were given the skis free of charge by a ski company. Women were also passionate about skiing. It is reported that in 1930, an 18-year-old Saas-Fee woman wore ski trousers to ski for the first time, which led to a real village scandal – women still had to wear skirts back then. Women continued to ski in skirts until 1938. Local men also ventured quite high up the mountains on their skis. In April 1946, there was a race from the Allalinhorn to Saas-Fee that would become a tradition. Of the nine starters, only five finished the first race.

So, how long after that did the cableway era begin?

In 1948, four locals Josef Supersaxo, Hubert Bumann, Robert Zurbriggen and Adrian Andenmatten decided that the time had come for a ski lift in Saas-Fee. They received a quote for a stable system of CHF 120,000. However, this was way too much for the village’s budget. They found a more modest solution in the form of a training lift for 16,500 francs. The first cable car ran from Saas-Fee to Spielboden from 1954.

This turned the Saas Valley into a year-round tourist destination.

Exactly. One of the four locals who initiated the first ski lift was Hubert Bumann, who was just 24 years old at the time. In the following decades, he became the driving force behind tourism in Saas-Fee and initiated pioneering projects such as the world’s highest underground railway, the Metro Alpin, in 1984. In Saas-Almagell, a chairlift to Furggstalden was built in 1965, along with a ski lift near the hamlet. The Saas-Grund ski area was only developed at the end of the 1970s, making it one of the most recent ski areas to be built in Switzerland.

Today, skiing and snowboarding is a year-round activity in the Saas Valley.

That it is. The best skiers and snowboarders in the world train on the Fee Glacier during the summer months. And in winter, 150 kilometres of groomed pistes are perfect for enjoying the snow.

The Saas Valley has also been home to some remarkable winter athletes.

Oh, yes, even some Olympic champions. In military patrol, the forerunner of today’s biathlon, four Saas athletes competed in a team at the 1948 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz: Arnold Andenmatten, the brothers Robert and Heinrich Zurbriggen and Walter Imseng. As Walter Imseng was taken ill just before the event, Vital Vouardoux from Grimentz stepped in. The team therefore only included three Saasers. On paper, Finland was the clear favourite, but the Valais team with the Saas trio took the gold medal and were welcomed back to Saas-Fee with a lavish celebration.

It was probably similarly exhilarating watching alpine ski races in the 1980s – because there was often a skier from the Saas Valley on the podium.

The 1980s were a big party in the Saas Valley. Thanks to Pirmin Zurbriggen. The skier from Saas-Almagell is one of the most exceptional athletes in alpine skiing with 40 World Cup victories and two Olympic medals, including one gold medal. In the Saas Museum, we not only have a racing ski but also the starting number and a ski boot from the Olympic downhill run in Calgary, Canada, which he won in 1988. Now let’s move on to a room with completely different clothing: traditional Saas costumes.

Traditional clothing

Traditional clothing

Traditional clothing

Women in the Saas region in the past probably weren’t allowed to just take whatever they fancied out of the wardrobe in the morning?

Definitely not. There were strict rules, particularly when it came to the choice of headscarf known as „lumpi“. You could tell from someone’s headscarf whether someone in the family had died recently and what stage of mourning the person was in. In the display case on the left you can see, among other things, a lumpi worn to mourn close relatives, a headscarf worn at the end of the mourning period and a headscarf for general Sundays.

Did the women in the Saas always wear a headscarf when they left the house?

Yes, almost always, when going to church or to work. Women only wore a traditional hat and dress on high feast days such as Corpus Christi, a priestly ordination or Christmas. When working in the fields, the headscarves served as protection from the sun. Women would then wear a less formal red cotton workday lumpi. The other lumpini were made of fine woollen fabric. There were several headscarves that could be worn on weekdays and Sundays. Single women could be recognised at Sunday mass by their white lumpi.

Did the women make their own headscarves?

No. The women bought their lumpini from the nearby Italian town of Domodossola for a long time. As well as headscarves, they also bought wedding rings and earrings and even copper kettles for cooking. People in Saas called the headscarves bought in Domodossola „Italian lumpini“. These came in different colours with different patterns. In the 1920s, the Bernese tradesman Knoer came to Saas-Fee during the summer holidays. He noticed that the local women were wearing „Italian lumpini“. He offered to make identical lumpini for the women. The Saas women agreed and were then able to save themselves the difficult journey to Domodossola. These colourful headscarves were then known as „Kner lumpini“.

You said that women wore a traditional costume on high church feast days. Was there as strict rules about this as there were about wearing the correct headscarf?

Yes, there were. The most obvious changes were made to the choice of ribbon for the traditional hat. This ribbon was adapted to the liturgical colours of the church year. On days commemorating martyrs, women wore a red ribbon, for example, and a purple one during Advent. Relatives would wear a white ribbon at baptisms, ordinations and funerals for children who were not of school age. However, not all Saas women could afford a Sunday dress. So, as an alternative, they took their best dress out of the wardrobe and wore it with a lumpi.

In the display case you can see the current Saas-Fee ceremonial costume, which is still worn today by members of the traditional costume association on selected days. Until when was it common for women to wear headscarves and traditional costumes?

Wearing the two-piece traditional costume with sleeved jacket, called schlutti, and a skirt declined rapidly from the 1960s onwards. However, there were still weddings in the 1990s where the bride wore the traditional dress. The mourning period headscarf was worn by Saas women until around 1968. The revolutionary spirit of modernisation then carried the lumpi away. However, until the early 2000s, there were still older women in Saas who wore traditional working clothes with headscarves – especially when working outdoors.

And the men?

The typical Saas men’s outfit in drill fabric was of little or no importance. When working in the fields, men also put lumpini over their shoulders to protect themselves from the sun. Now let’s go to the top floor of the Saas Museum.

Sacred landscape

Sacred landscape

Sacred landscape

We have now reached the top floor of the Saas Museum.

There’s a very Christian atmosphere here again.

That’s right. This collection brings together altars and church artefacts from various Saas churches. It was decided not to use the old altars in the current Saas-Fee parish church, which was consecrated in 1963 and designed by architect David Casetti. So, 20 years after the church was consecrated, they were given a place in the Saas Museum.

Is that the Valais saint Theodul on an altar?

Well spotted. The largest altar in the room is a Theodule altar from the 18th century. This altar used to be in the Chapel of St Theodul built in 1666, one of the early church buildings in Saas-Fee, and in the former building of the current church between 1894 and 1963. Theodul is the first known bishop of Valais and was the patron saint of hail, frost and lightning, all forces of nature from which the locals in the Saas Valley hoped to be protected. The lower figure in the altar is Theodul. He is shown as a bishop.

And who are the figures on the altar above St Theodul?

On the left is St John Nepomuk, a 14th century Bohemian priest and martyr. He was not canonised by Pope Benedict XIII until 1729, around the time the altar was built, which could explain the figure on the altar. He has the symbol of a crucifix. At the centre, the apostle Peter holds his symbol, the keys. It is not known who the saint on Peter’s right could be. It is probably the apostle John, who is also often depicted with the symbol of a crucifix.

I can see an impressive cross near the stairs, which was probably used at funerals.

Exactly. This Tumba cross from the 17th century was first used in the Chapel of St Theodul. Until 1983, this cross was displayed at funerals, during Holy Week, on Ember days and at memorial services for the dead. With depictions of the death of the king, bishop and pope, the cross reminds us that we are all mortal and equal in death.

And what’s with the pretzel machine?

It’s not a pretzel machine, it’s a wafer machine. For a long time, priests made the wafers for services themselves.

Let us now go to the last room, where we can see the work of a local artist.

Werner Zurbriggen Art Space

Werner Zurbriggen Art Space